Object Permanence

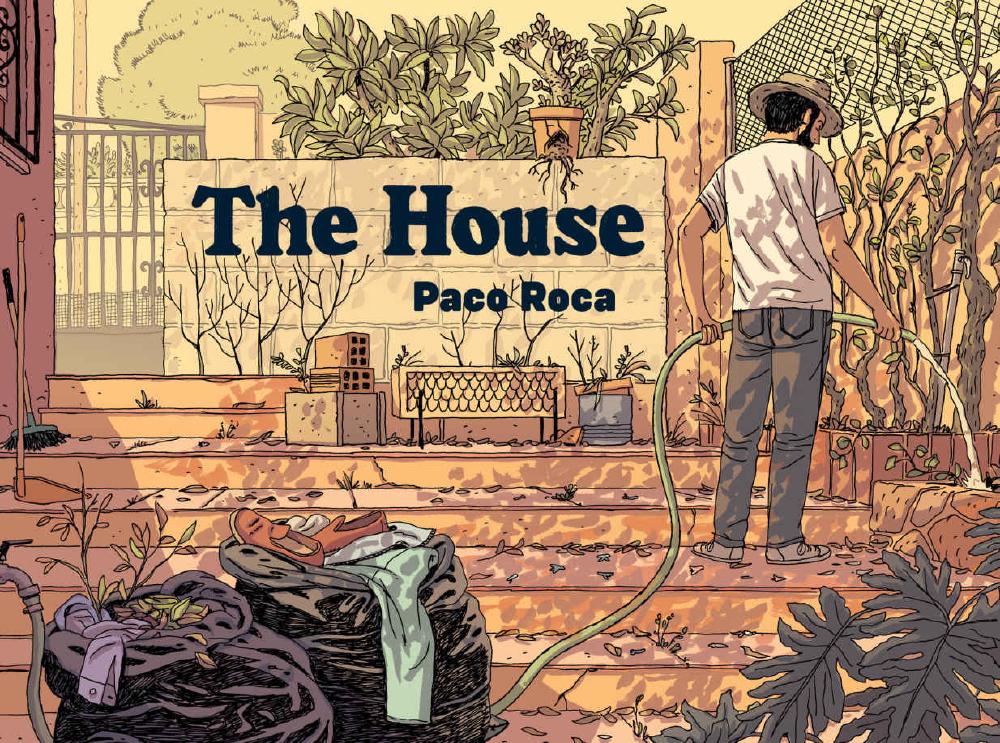

I read The House this past week. The book tells the story of three siblings who reconvene in the house where they grew up, just a year after their father’s passing. The decrepit building stands as a container for everything the father owned and built, and as a stage for the memories each sibling has of their father. This review by Daniel Elkin does a great job at capturing the subject and the mood of the book:

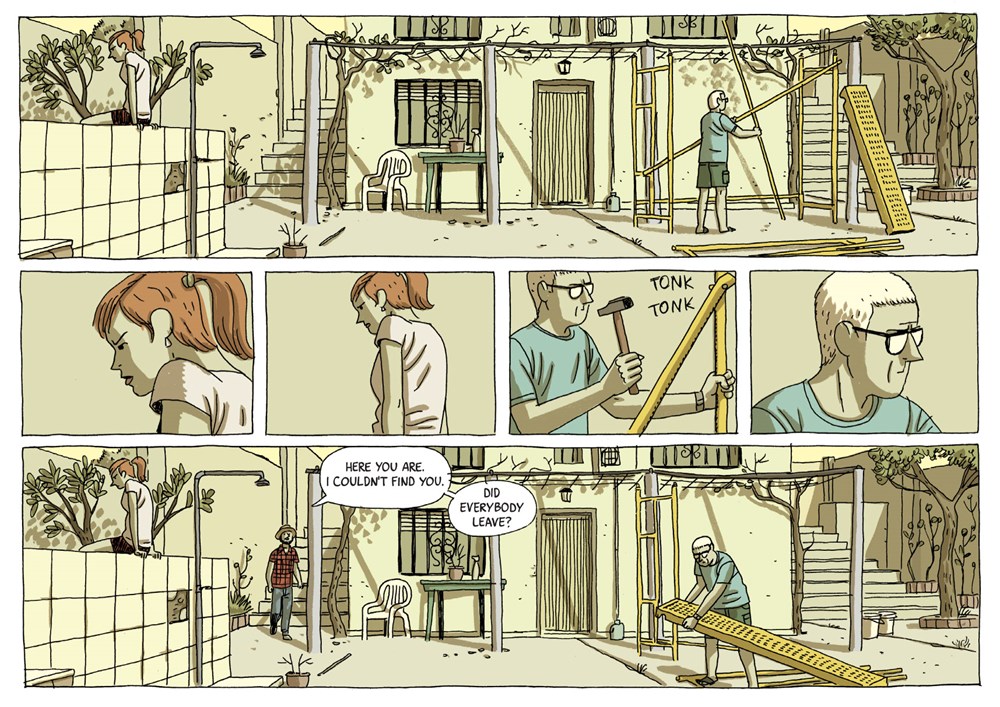

The father built the house as a reflection of who he wanted to be. Part of the underclass due to poverty, the father had put his aspirations of place and status into the structure, pulling the entire family into the exercise. His children at the time had little to no appreciation for this, viewing the family vacations there as akin to a work camp rather than any sort of legacy building. It is only in the absence of the father that they begin to understand what the house meant to him. And as they begin to understand the house, so too do they begin to understand the father.

Object permanence — the idea that things exist independently of our perception of them — is a simple concept that is key for infants to build psychological safety. The knowledge that your things are where you left them, that objects belong in a location. For the siblings, the object blends with the location and, in time of mourning, embodies the person who passed away. In spite of having slowly distanced themselves from it, this place remains a staple which, sooner or later, will need to be dealt with. The moment they do is when they truly internalize that the house still stands but their father is absent.

My father passed away recently — he wasn’t a healthy person by any stretch of the imagination but his death came very suddenly and unexpectedly. Some of the themes that the book evokes struck a chord with me, as they were reminiscent of my own experience.

Me and my siblings reunited in that moment, and it became evident how different each of our personal situations is (though I can say with confidence we have gotten closer since then). We went through our father’s files and wondered why on Earth he kept every single ticket and fine he got over 30 years (many dozens of them — we had no idea how bad a driver he actually was). We laughed while spending hours sifting through his book collection because we had a strong suspicion he was hiding a stash of cash there (no secret piggy bank, it turned out). I struggled with the idea that children to come will not meet their grandfather (I still do).

I believe there’s something about the collective grieving process that is distinctly different from the one you go through as an individual. The House is as much an ode to a patriarch as it is to siblinghood, as well as a call for everyone to build the tools to remember closed ones by. It’s also an invitation to focus on what lies ahead. I lost track of the source but I recently read someone claiming, in essence, that we spend too much time trying to be good descendants when we should instead be setting models for younger ones to be inspired by. I think about this a bunch these days.